New Deakin and University of Melbourne research has put a spotlight on the health of Port Phillip Bay, showing the effects of the millennium drought has almost wiped out kelp forests in the bay’s north.

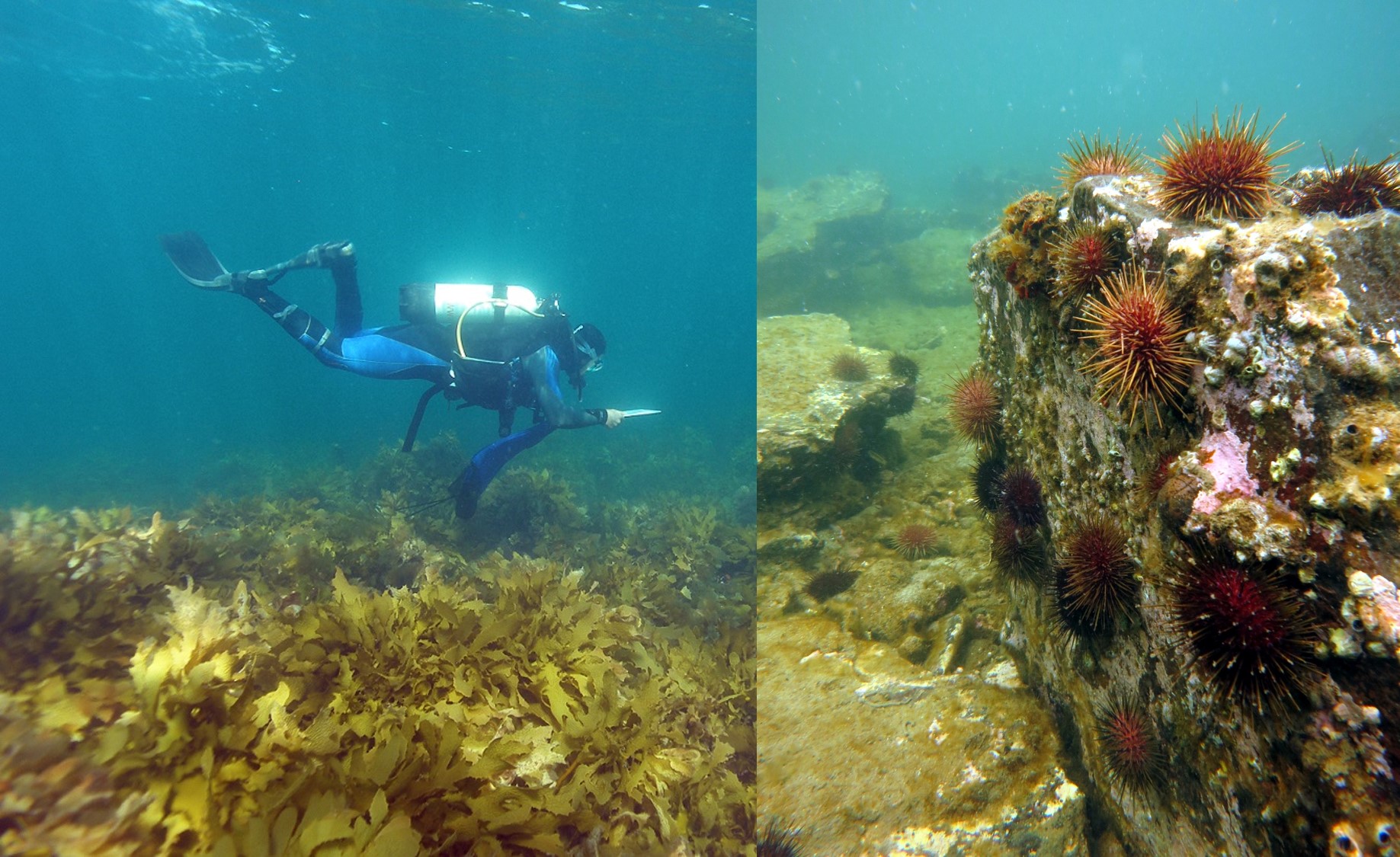

Lead author Dr Paul Carnell, an associate research fellow in Deakin’s Blue Carbon Lab, said the drought’s decline in rainfall coupled with an increase in temperatures had coincided with an explosion in the numbers of destructive sea urchins in Port Phillip. The urchins had effectively marched across sections of the bay, eating everything in their path.

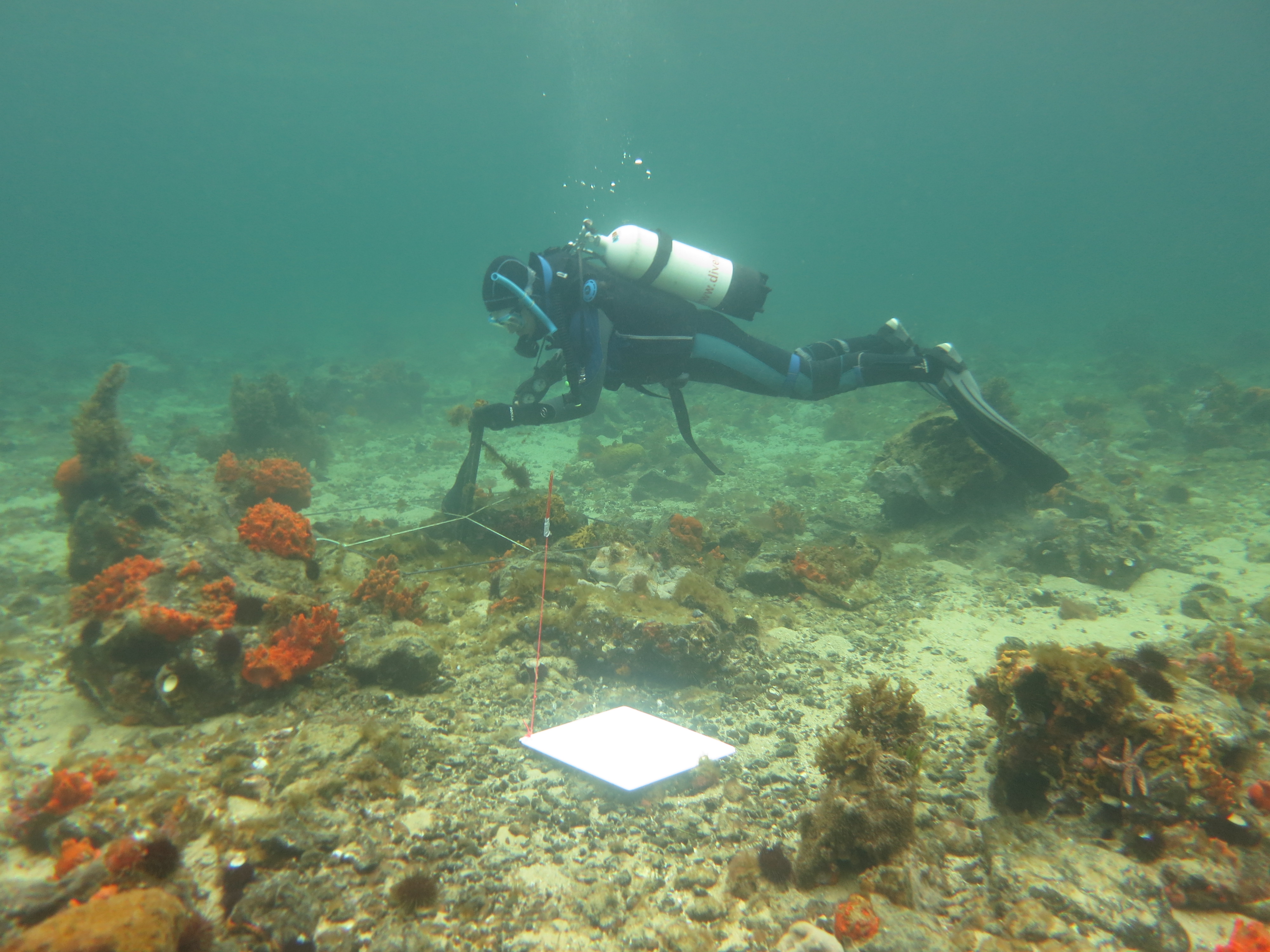

The study, published in the journal Estuaries and Coasts, documents for the first time the loss of kelp forests in Port Phillip Bay over the past 60 years, using historical information and aerial photographs, along with new data collected by SCUBA divers.

Dr Carnell said the data showed the health of Port Phillip Bay had declined dramatically over that time, with 90 per cent of kelp forests around Williamstown, Point Cooke and Beaumaris wiped out.

“Kelp is a critical indicator of the health of Port Phillip Bay. It’s the habitat for a range of fish and invertebrates like abalone, that we like to see or fish,” he said.

“Our study shows the huge decline in kelp was when we had the big drought from 1997 to 2009. During this period there was a one degree increase in average daily maximum temperature and 137mm less rainfall than the long term average.

“With the changes in the environment we started to see a decline in kelp, but when kelp started declining the bay’s urchins ran out of food and had to change how they ate. So they couldn’t just sit there anymore, they had to move around to find their dinner and that really drove the final loss of kelp.

“Now the northern part of the bay where kelp forests once predominated, are mostly covered by what we term ‘urchin barrens’. While there have been areas of urchin barren in the bay in the 70s and 80s, they rapidly expanded towards the end of the drought.

“While the numbers of urchins have dropped back after that spike, they can subsist on some small weedy species and the small amounts of kelp that return, but they eat it straight away before it gets a chance to grow back properly.

“Even today, there’s basically no kelp left in Point Cook and Williamstown regions, but fortunately Beaumaris has started to show some recovery.

“The alarming thing is if that’s what has happened with one degree warming, it’s only going to be made worse as climate change continues.”

Dr Carnell said there were currently projects underway funded by the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning’s Port Phillip Bay Fund to try to encourage kelp forests to return to the northern parts of the bay.

The work includes the planting of kelp, as well as an urchin cull, led by the University of Melbourne with Deakin University, and supported by Parks Victoria and community volunteers.

A year into the culling project, up to 40,000 urchins have been destroyed but Dr Carnell said that’s barely scratched the surface.

“The scale of the task is huge, in Point Cook there are 20 urchins per square metre of reef, so it’s going to take a lot of work before we start noticing an improvement,” he said.

“Unfortunately urchins are really good at surviving in times of famine. We often get asked why we can’t fish them and sell the roe, and that’s because these urchins are in poor condition out on reefs with nothing to eat, so the roe is no good. They’re surviving but they don’t taste good.”

The Scientist

Dr Paul Carnell is a research fellow at the Blue Carbon Lab, Deakin University. He researches kelp forest dynamics and #BlueCarbon accumulation in coastal and inland wetlands.

Media Contact

Elise Snashall-Woodhams. Senior Media Coordinator, Deakin University

P: 03 924 68593 M: 0436 409 659 E: e.snashallwoodhams@deakin.edu.au T: @DeakinMedia