SUNDAY STAR TIMES

| Auckland, NZ | Dec 16, 2018 | By Laine Moger

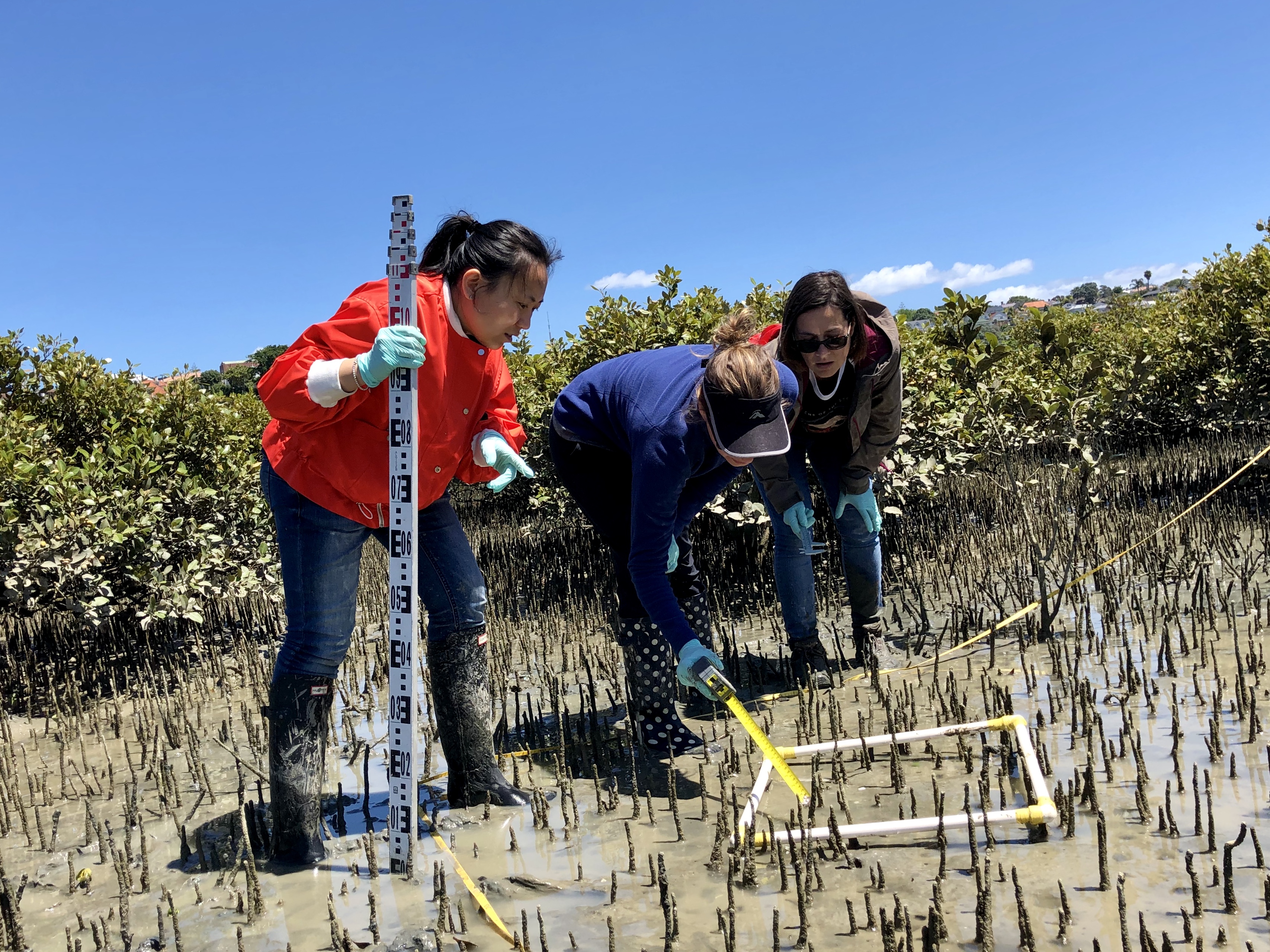

An eye-watering suction sound burps from beneath the mangrove mud, as banker Chris Russell attempts to dig a hole big enough to plant a Lipton tea bag.

It’s a different change of pace for the HSBC chief executive who is wading through sticky mangrove wetlands.

The evidence of his involvement in this morning’s science experiment is already showing on his muddy trousers. The same trousers he will be wearing back to the office that afternoon because he didn’t bring a spare.

He counts himself lucky, his colleague across the plain has lost a gumboot. Mangrove mud is incredibly unforgiving.

TeaComposition H2O has been implemented at over 350 sites across the world, but this is a New Zealand-first contribution. The idea is to bury Lipton Green and Rooibos (red) teas for a few years before digging them up again to study their carbon decomposition rates.

By doing this scientists’ will be able to identify the aquatic ecosystems such as our mangroves that have a greater potential to store carbon. These ecosystems can then be used to help mitigate climate change.

But this is one of many innovative climate change solutions that are being implemented both in New Zealand and abroad in an attempt to keep the rise in global temperatures below 1.5C.

In New Zealand, organisations such as the World Wildlife Fund NZ wants to cut emissions completely and replace it with renewable energy while 350 Aotearoa is campaigning to get our banks to stop investing billions of dollars in the fossil fuel industry.

Greenpeace campaigner Amanda Larsson says their focus is on trying to get the Government to offer over 500,000 interest-free loans to households so they can install solar panels and batteries in the next ten years. They believe this will contribute 1.5 gigawatts of new clean power and 3 gigawatts of grid-stabilising battery storage to the country’s electricity grid.

Meanwhile, renewable energy and how to farm for it is something that appears to have the most potential when it comes to innovative climate change solutions. Various global companies are sinking their teeth into this possible gold mine by finding new ways to produce energy through solar, wind, hydro-, geothermal and tidal sources.

For example, organic solar panels that can be printed using conventional printers and costs less than $10 per square meter was recently launched in Australia while a 15-year-old girl from Azerbaijan has created a device that can generate electricity from rainwater. And this is beside the world’s largest operational offshore wind farm in the United Kingdom or Facebook’s attempt to deliver the internet via solar-powered drones.

BLUE CARBON ECOSYSTEMS

Back in Bayswater in Auckland’s North Shore, Doctor Maria Palacios, from Blue Carbon Lab, guides a group through bursts of summer thunderstorms in the mangrove swamp.

The mud went past the “comfort zones” of most of them, Palacios says, a waterline of mud sitting mid-thigh on her tearaways as she speaks.

The misunderstood mangrove is a crucial, game-changer in reducing climate change, she explains.

Simply put, mangroves are expert suckers, both gumboots and carbon alike.

They suck carbon from the atmosphere 30 to 40 times more efficiently than a rainforest.

But mangroves are not New Zealand’s most popular ecosystem.

They’re sticky, smelly, muddy expanses of brown sludge that hug the edges of New Zealand’s beautiful oceans like a clingy, unattractive partner.

Kiwi landholders are often applying for permits to chop them down because they block the view to the ocean or boat access.

But mangroves could be the key to offsetting Auckland’s rather large carbon footprint.

Sam Judd from Sustainable Coastlines says if there was one thing that New Zealand should get behind concerning climate change it should be wetlands.

“Reconstructed wetlands are the way forward,” he says. “They are like kidneys for the land and water and hotspots of biodiversity.”

Palacios agrees, saying it’s in the really sticky, smelly part of the mangrove where the magic happens.

Mangroves are among Earth’s most efficient carbon sinks because they capture carbon dioxide, what humans breathe out, and other gaseous carbon compounds from the atmosphere and locks it away in the ground. This process is called ‘blue carbon’.

Blue carbon ecosystems also provide other vital services: Enhancing biodiversity, supporting fisheries, and protecting shorelines against extreme weather events.

The Blue Carbon Lab, an Australian research group based at Deakin University, specialises in capitalising on this ‘blue carbon’.

NEW ZEALAND’S MANGROVES ARE UNIQUE

Two types of Lipton tea bags have been used for the experiment: green tea and red (Rooibos) tea.

Rooibos tea leaves are more woody and barky, and should technically take a long time to decompose. Green tea is leafier and should degrade faster.

Each tea bag has been painstakingly weighed, usually around 2 grams, and marked it with an individual number ready for planting.

The spots are then marked with a flag to dig up later on in three, six or 12 months later.

How much the tea bag has decomposed is a measure of how good the wetland is. The less decomposition – the better the wetland.

“Ideally we want the tea bag to come out of the ground the same it went in, still weighing 2 grams,” Palacios says.

Dr Carolyn Lundquist, a marine ecologist at NIWA, explains identifying the good from the bad wetlands can be helpful for a few reasons.

The factors that make a good wetland can be used to regulate other wetlands.

Also, finding out how much carbon mangroves store, can help pinpoint where New Zealand’s most valuable mangroves are.

That way, scientists can tell the government which mangroves to prioritise in protection.

Mangrove forests in New Zealand are unique, because we are the only country in the world where they are expanding at a crazy rate of 3.2 per cent each year, she says.

Yet despite this, mangroves remain super misunderstood by the public.

“Mangroves do a lot of things that we appreciate after we lose them. It’s about finding the mangrove to non-mangrove balance.”

While the carbon-sucking benefits of mangroves are not new, the tea bag is the innovative part of this climate change solution, Lundquist says.

“I’d never have predicted tea bags,” she admits.

“The tea bag provides global compatibility because it is a barometer that stays the same when all mangroves behave differently. In different climes, and habitats.”